Standard No. 1:

Buyer circumstances may shape financing terms, but they do not mitigate the developer’s risk exposure.

In this edition of The Boldmen Standards, we return to the first principles. The business of real estate financing is not voided by empathy. Whether delivered by a bank, a seller, or a developer, capital extended without interest is still capital at risk. We uncover a tacit but costly assumption behind staggered down payments and rent-to-own structures, which is, that flexibility is risk-neutral. It is not. There are always trade-offs. Flexibility may be considered for sound strategic reasons: to improve market absorption, meet affordability targets, or reduce pipeline friction. But none of these cancels the financial exposure the developers take on. The capital is still at risk. The time value of money still applies. And if they’re not earning interest on deployed funds, they’re incurring an unpriced loss. We unpack those hidden exposures, model the yield erosion beneath delayed equity, and outline practical frameworks for regaining control.

Introduction

In most West African financial circles, flexibility is marketed as a virtue. And in a nation like Nigeria, where affordability gaps, cash-flow volatility, and informality dominate the housing market, offering borrowers staggered down payments and rent-to-own payment structures feels humane, practical, and sometimes even patriotic(?)

But as with many well-intentioned financial accommodations, there’s a hidden cost. And like most hidden costs in finance, it doesn’t show up on a balance sheet.

This is for the mortgage underwriters, CFOs, and strategy officers who understand that the financing structure influences the yield outcomes, and who also understand that the laws of compounding do not care about their social impact goals or their customers’ feelings. If they choose to ignore them, they’d learn, and they’d learn the way!

Let’s get right into it already!

The Cost of Good Intentions

A developer offers financing on a property valued at ₦10 million to a qualified buyer. The loan-to-value (LTV) ratio is 80%, which means the buyer is expected to contribute ₦2 million as equity/down payment. This down payment is intended to serve as a first-loss buffer, providing protection to the developer in the event of foreclosure or a decline in property value.

Property Value: ₦10,000,000; Interest: 15% (monthly); Maturity: 20 years.

However, many buyers, especially first-timers, do not have the resources to pay the ₦2 million upfront. So developers often offer a workaround by splitting the down payment into staggered tranches over a fixed time period, ranging from 12 months to 36 months!

From the regulatory bodies’ perspective, this, this is Inclusion! From the buyer’s perspective, this is Access. But, from the developer’s perspective, this is a concessionary, interest-free loan layered beneath the mortgage.

And, to make it more interesting, it is usually not priced into the financing model structure!

Now, the developer is not really disbursing ₦10 million in cash on Day 1, however, they are effectively extending the full economic value of the property by allowing the buyer to take possession upfront. In doing so, they begin earning interest on only ₦8 million, while the remaining ₦2 million in buyer equity is scheduled to be paid in instalments over time. This creates a capital exposure without yield, resulting in a drag on return that quietly compounds over the holding period.

Some developers try to model the full disbursement on their spreadsheets by attempting to fully amortize the full ₦10 million (instead of only the ₦8 million that accrues interest), you know, to help manage their exposure and earn interest on the entire cash outlay. But doing this comes at a cost, as there are always trade-offs:

- By modelling the entire value of the property, the monthly payments inevitably increase, pushing up the payment-to-income ratio for the borrowers, and possibly breaching underwriting thresholds. The result? The very folks the product was designed for, middle-income first-time buyers, get disqualified at the door.

- By increasing the LTV ratio to approx. 99.9% (effectively eliminating the equity requirement), developer sees their capital exposed to potential loss, as there is barely a cushion if the value of the property falls, leaving the developers with the short end of a badly structured stick.

So the developers are left with a false dilemma: model the risk properly and exclude the target market, or underprice the risk and expose your capital.

The Rent-to-Own Mirage

Another form of silent equity financing is the rent-to-own model. And it is fast gaining popularity in Nigeria. At first glance, it looks clever.

- The developer keeps ownership.

- The tenant-buyer pays rent for three years.

- At the end of the period, the tenant-buyer is allowed an option to convert to a mortgage at a pre-agreed price and interest rate.

Easy-peasy. No vacancy. No paperwork bottleneck. Now, if we look deeper, we see that that that rent isn’t just rent. It is deferred equity, dressed in softer language. And this is made more true, when you realize that leasing is, really, the financial equivalent to taking out a mortgage.

So, while the buyer is building equity (via rent), the developer bears the time risk on the capital, again, without earning interest on it. The rent resembles a mortgage in both amount and behavior. And the capital outlay remains uncompensated until the buyer converts.

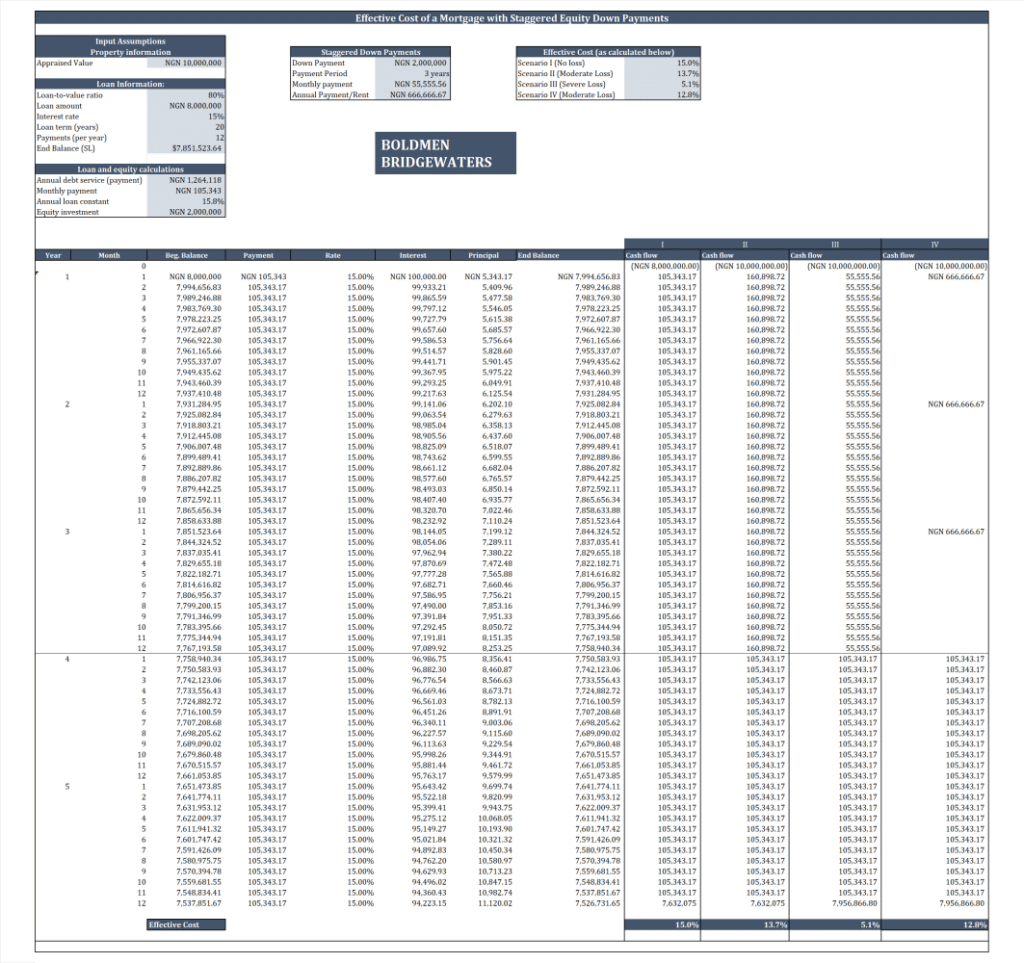

Model for Scenario I, II, III and IV.

To illustrate using the model above, consider the following 4 scenarios, each a variation on how the equity/down payment is funded and how yield/return to the developer is impacted.

Scenario I: Upfront Equity

The buyer pays the full down payment upfront and immediately begins monthly repayments to amortize the loan. On a ₦10 million property, the buyer contributes ₦2 million in equity, and the developer extends financing on the ₦8 million at 15% nominal interest. In this case, the structure is sound. The risk buffer is intact. The lender earns the full yield.

Outcome: No exposure. Developer earns full return (Effective yield to developer = 15%).

Scenario II: Staggered Equity

The buyer cannot meet the ₦2 million equity/down payment requirement upfront. Instead, the developer agrees to staggered equity contributions, ₦2 million spread across 36 equal monthly installments. These payments are structured to run in parallel with the mortgage amortization on the ₦8 million loan. On the face of it, this is workable. But underneath, the structure quietly erodes the developers yield. Because, the equity component, ₦2 million, earns the developer no interest. Yet the capital is exposed from Day 1.

Outcome: Partial yield realization. Delayed down payment recovery (Effective yield drops to 13.7% from the nominal 15%).

Scenario III: Rent-to-Own (Monthly Rent Installments)

Here, the developer offers a rent-to-own pathway. The ₦2 million equity is broken into 36 equal monthly rent payments. The buyer pays monthly, occupying the home as a tenant. At the end of three years, the buyer may elect to convert to a formal mortgage for the ₦8 million balance. During this period, the “rent” technically builds equity. But really, it functions as capital extended without return.

Outcome: Effective yield suffers significantly (drops to 5.1%).

Scenario IV: Rent-to-Own (Annual Rent Installments)

This variant allows the buyer to make three annual rent payments of approx. ₦667k each. These annual rent payments accumulate toward the ₦2 million equity requirement. After three years, the tenant may opt into the mortgage. This structure compresses exposure into longer, lumpier periods.

Outcome: Effective yield drops to 12.8%.

Now, you’d notice from the model that Scenario III and IV, though similar in structure, yield staggeringly different returns to the developer.

Scenario III yields only 5.1% (a staggering drop from the nominal 15%) because the monthly payments, though earlier, are too small to offset the developer’s exposure or create re-investable value for them. The cash in-flows are in tiny bits (via monthly payments), and due to the time value of money, each of those cash inflows are worth far less in present terms. Scenario IV, by contrast, delivers larger lump sums annually, allowing the developer to recover cashflow in meaningful blocks and preserve more of its present value (by affording them the opportunity to invest the lump sums and to earn substantial interest on them). In finance, it’s not just when money comes back, it’s how much comes back, and how soon.

What This Really Is

Whether through staggered down payments or rent-to-own setups, the developer is effectively making two loans:

- A standard interest bearing mortgage, and

- A silent, non-interest-bearing (unsecured?) loan.

This second loan is not accounted for. It usually does not appear in origination fees or pricing models. But it is very real. And over time, it acts as a drag on the capital efficiency for developers offering these financing structures.

How Developers Can Manage These Risks

Now, let’s not misread the situation. Developers exposing themselves to latent losses like this is commonplace. But, it is, really, a skill issue. The exposure is manageable and can be strategically adjusted for. To reduce their exposure, developers should consider a disciplined combination of the following:

- Developers may consider charging strategic origination fees. These fees, charged at initiation and embedded into the value of the property, can help to boost their returns. If used strategically, they can partially offset the lost income from delayed equity and help improve their nominal return. But these fees must be applied transparently, with full disclosure. As hidden charges will only erode trust.

- Developers may consider pricing the annual/monthly rent on the Rent-to-Own structure with a built-in premium that compensates for the opportunity cost of deferred equity.

- Shorten the duration for the staggered payments to not more than 3 months. This prevents long-term float of capital without return. This is the most important!

Final Thoughts…

In developed societies, government-sponsored mortgage insurance entities and private mortgage insurance companies exists to underwrite the developer’s risk of loss when buyers cross the 80% LTV threshold. However, in Nigeria’s nascent real estate market, where such entities are absent, developers must maintain a balance between accelerating market absorption and preserving risk-adjusted returns. To thrive, they must strategically harmonize the market demand with prudent risk management.

Knowing that the true measure of institutional excellence does not depend on the volume of homebuyers served, but in the delicate balance between financial inclusion and sustainability. The most resilient developers will be those able to expand access to credit while safeguarding their own stability. This nuanced equilibrium requires strategic acumen, rigorous risk assessment, and a deep understanding of the market’s intricacies.

About the Author

This edition was compiled by Da-tonye Bright Agborubere, the Lead Solicitor and Head of Research for Boldmen Bridgewaters Advisory.

Join The Discussion